In the discourse surrounding economic justice and public policy, it is common to encounter skeptics of established narratives. Skepticism, when grounded in inquiry and evidence, is healthy. However, a recent exchange on a professional forum highlighted a troubling trend: the misappropriation of Henry George’s philosophy to support anti-scientific conspiracy theories about climate change.

The discussion centered on nature-based solutions for sea-level rise and flooding in Puerto Rico, yet it drew an unexpected response from a self-described Georgist who rejects the reality of climate change. A commenter argued that man-made climate change is not real, calling it a political coercion tool like the “manufactured” COVID-19 crisis. Most notably, the commenter advised legitimate students of economics to “discern reality from fiction by studying Progress and Poverty by Henry George.”

Invoking Henry George to defend climate denialism is a profound misreading of Georgist philosophy. It conflates a healthy distrust of government market interventions with a denial of scientific consensus on increasingly perilous climate threats. To set the record straight, we must explore why the “prophet of San Francisco” is not an ally to climate deniers, but instead offers a clear, elegant economic framework for protecting the planet that sustains us.

The Misunderstanding of “Manufactured Crises”

The commenter’s argument rests on the premise that modern crises—from pandemics to global warming—are fabricated solely for wealth redistribution. There is a grain of truth in his argument: wealth redistribution does occur during crises.

As students of political economy know, the COVID-19 pandemic saw a massive transfer of wealth to billionaires, while small businesses and the working class suffered. Similarly, the “green” economy has its share of rent-seekers lobbying for subsidies rather than genuine solutions (Williams & Studies, 2025).

However, recognizing that opportunists exploit crises is different from claiming the crises themselves are fiction. Henry George did not teach us to ignore the physical world; he taught us critically examine ownership claims to nature and the moral limits of private appropriation. When a conspiracy theorist cites Progress and Poverty to argue that a changing climate is a hoax, they miss George’s central insight: that our economic system allows private interests to shift the environmental costs of production onto society at large.

Land, Nature, and the Commons

To see why Henry George would likely have advocated for climate action, we need to understand what he means by “land.” George defines land as all natural endowments that exist independently of human labor; by extension, he includes all natural resources, such as soil, terrain, water, minerals, forests, and more (George, 1879, p. 335). For George, land encompasses not only the ground beneath our feet, but all natural materials, forces, and opportunities: the minerals in the earth, the fish in the sea, the electromagnetic spectrum, and even the atmosphere’s capacity to absorb waste. These are not created by any individual, and therefore belong equally to all.

As George write: “For we cannot suppose that some men have a right to be in this world and others no right” (1879, p. 336). He continues:

“The equal right of all men to the use of land is as clear as their equal right to breathe the air – it is a right proclaimed by the fact of their existence” (George, 1879, p. 336).

George’s fundamental maxim is that the elements of nature belong to the community as a whole. His expansive definition of land closely resembles what economist now describe as public goods – resources that are “non-rivalrous and non-excludable” (Public Goods Explained, n.d.). When such shared goods are exploited in ways that exclude others from their use or enjoyment, the result is a familiar problem, often described as the “tragedy of the commons” (Hardin, 1968). When an industry pumps carbon dioxide into the atmosphere, it is enclosing the commons just as surely as a landlord who fences off a pasture. A major issue in current environmental and climate justice discussions is that industries often use shared resources freely, without paying for the economic impact of their depletion (Gosseries, 2004; Atkins, 2018). At its core, this is a classic free-rider problem (Free Rider Problem, n.d.).

The Georgist Remedy vs. “Political Coercion”

The commenter views climate policy as a tool for government control, decried as “political coercion.” Coercion, however, is a contested concept, so it is worth pausing to consider its meaning. While coercion is commonly framed as government constraint (Anderson, 2020), political theory recognize forms of coercion that go beyond state force. As Arthur Ripstein notes (2004), non-consensual interference with another person’s property is itself coercive. If, as Henry George argued, the benefits of nature are a common right shared by all, then degrading or appropriating those benefits without consent interferes with others’ freedom and rights. Pollution does exactly this by infringing on the rights of others to inhabit a healthy planet.

Interestingly, Henry George offered a solution that relies on market mechanisms rather than bureaucratic command-and-control.

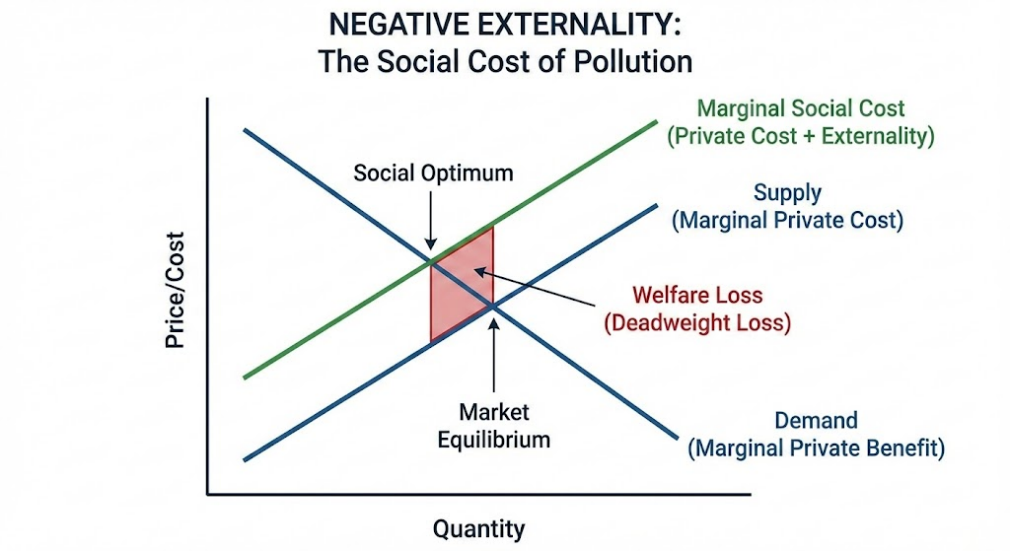

Caption: This diagram is a basic economic model that illustrates why untampered markets can fail. The diagram shows that markets on their own produce too much pollution. Without policy solutions to correct this, polluters do not pay the full cost of the harm they cause – health impacts, premature death, economic disruption, environmental destruction, and the loss of livelihoods and homes. Without policy interventions, these are spread across society instead of borne by the polluters.

Current environmental policy relies on complex regulations and policies as sticks and carrots to motivate change. My critic rightly notes that these can be the very things that breed corruption and inefficiency (Why Is Corruption Rampant in Environmental Sectors?, 2024). A Georgist approach, however, offers a simplified policy solution. If the atmosphere is common property, then those who degrade it owe “rent” to the community. The polluter pays.

This is the logic behind a Carbon Tax and Dividend (or “Green LVT”). Taxing the pollution at its source charges a user fee for the consumption of natural opportunities (Climate Leadership Council, 2019). Like Henry George’s land value tax, carbon pricing treats the atmosphere as a shared inheritance, charges for its private use, and returns the value to society rather than penalizing productive activity. Both the Green LVT and the LVT reflect a similar principle: markets work best when the private use of common natural wealth is priced and its value shared.

Asking polluters to pay the full social cost of their emissions and contamination is the ultimate defense of the public’s right to a clean, healthy, and sustainable environment, a human right formally adopted by the United Nations General Assembly in July 2022.

Adaptation is Not a Conspiracy

What prompted the critic was my blog on climate adaptation, which examined emerging opportunities in adaptation and the challenges they pose for community-based organizations. More broadly, climate adaptation refers to actions such as building seawalls, upgrading drainage systems, managing human migration, and reinforcing power grids, along with other built and nature-based solutions. It also includes the relational and social ways communities cope with changing hazard exposures. These are tangible and behavioral necessities driven by observable data and scientific consensus.

Denying the physical phenomenon of the Greenhouse Effect, does not make the sea level stop rising. It merely ensures that when disaster strikes, the burden will fall disproportionately on the poor who cannot afford to move to higher ground or insure their assets (Alston & UN. Human Rights Council. Special Rapporteur on Extreme Poverty and Human Rights, 2019; IPCC, 2023).

Caption: Hurricane Maria has claimed more than 1,000 lives in Puerto Rico and displaced tens of thousands of others, an example that man-made disasters disproportionately affect the poor. Photo credit: Momsrising.org

Henry George wrote Progress and Poverty to explain why poverty persists amidst advancing wealth. He identified that among the key issues was the private capture of the natural world. Today, as we face a crisis that threatens the habitability of that world, his work continues to have relevance.

To cite George in defense of inaction is to ignore his moral clarity. He did not write to comfort those who wish to exploit the earth without consequence. He wrote to demand that the value of the natural world be shared by all. In the 21st century, that means acknowledging the reality of our changing climate and applying the principles of justice to the air we breathe, just as we do to the ground beneath our feet.

References:

Atkins, J. S. (2018). Have you benefitted from carbon emissions? You may be a “morally objectionable free rider”. Environmental Ethics, 40(3), 283-296. Retrieved December 18, 2025 from https://www.academia.edu/download/84497924/atkins.pdf

Alston, P. & UN. Human Rights Council. Special Rapporteur on Extreme Poverty and Human Rights (Eds.). (17). Climate change and poverty: Report of the Special Rapporteur on Extreme Poverty and Human Rights. UN. https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/3810720

Anderson, S. (2020). Coercion. In E. N. Zalta & U. Nodelman (Eds.), The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2020). Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2020/entries/coercion/

Climate Leadership Council. (2019, January 16). Economists’ statement on carbon dividends: Bipartisan agreement on how to combat climate change. The Wall Street Journal. https://www.wsj.com/articles/economists-statement-on-carbon-dividends-11547682910

Free Rider Problem: What It Is in Economics and Contributing Factors. (n.d.). Investopedia. Retrieved December 18, 2025, from https://www.investopedia.com/terms/f/free_rider_problem.asp

George, H. (1879). Chapter 1. Injustice of Private Property in Land. In Progress and Poverty: An Inquiry into the Cause of Industrial Depressions and of Increase of Want with Increase of Wealth: Vol. VII Justice of the Remedy (25th ed., pp. 331–344). Doubleday, Page & Company. Retrieved December 18, 2025, from https://oll-resources.s3.us-east-2.amazonaws.com/oll3/store/titles/328/0777_Bk.pdf

Gosseries, A. (2004). Historical emissions and free-riding. Ethical perspectives, 11(1), 36-60. Retrieved December 18, 2025 from https://www.academia.edu/download/30428610/Historical_emissions_and_free-riding.pdf

Hardin, G. (1968). The Tragedy of the Commons. Science, New Series, 162(3859), 1243–1248. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1724745

Intergovernmental Panel On Climate Change (IPCC). (2023). Climate Change 2022 – Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability: Working Group II Contribution to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (1st ed.). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009325844

Public Goods Explained: Definition, Examples & How They Work. (n.d.). Investopedia. Retrieved from https://www.investopedia.com/terms/p/public-good.asp

Ripstein, A. (2004). Authority and Coercion. Philosophy & Public Affairs, 32(1), 2–35. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/3557980

Wealth of world’s 10 richest men doubled in pandemic, Oxfam says. (2022, January 17). https://www.bbc.com/news/business-60015294

Why Is Corruption Rampant in Environmental Sectors? (2024). Sustainability Directory. https://pollution.sustainability-directory.com/question/why-is-corruption-rampant-in-environmental-sectors/

Williams, B. T., & Studies, E. (2025). Semblance of Sustainability: A Multidisciplinary Analysis of Corporate Greenwashing in the United States. Retrieved from https://research.library.fordham.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1212&context=environ_2015