The following is part 1 of a two-part discourse by David Southgate during South Puerto Rico Community Summit (January 24, 2026) held at the Centros Sor Isolina Ferré, Santa Maria de la Luz Hall in Ponce, Puerto Rico, where 103 community members attended. Present also were government officials from Ponce’s Municipality Planning Office, the Puerto Rico Department of Natural Resources, and the Environment (including the director of the island’s Coastal Maritime Zone Management Office), as well as the US EPA.

Good morning, everyone. Last year, I had the opportunity to present our community work on climate change at a conference at Columbia University in New York [MR2025: Mobility, Adaptation, and Wellbeing in a Changing Climate]. I have presented in various forums for many years, but I must tell you, this is the first time I feel nervous, because I am presenting in my own community. I want to own that nervousness, and I hope you enjoy the thoughts I am about to present.

The Local Reality of Climate Change

We will discuss several topics: the reality of climate change, the challenges we face in the local context, and the fact that climate change adaptation must occur at the local level. My graduate studies specialize in community development, where our unit of analysis is the neighborhood. It is a meaningful coincidence that my life has brought me to this hyper-local context, speaking on climate change in the same community where I practice through my participation in Un Nuevo Amanecer, as a board member and an advisor to our president.

Recently, I published an article for the Progress & Poverty Institute about my work here in La Playa. I received a very strange comment from someone who saw the publication and claimed that “climate change is a hoax.” We must recognize that some people believe it is not real. Skepticism is important because it gives us critical power, but skepticism without foundation helps no one. Denying climate change will not stop the rising sea levels, nor will it stop the torrential rains that flood our houses and streets. If we persist in denying reality and the global scientific consensus, the people most impacted will be the poor—those with the least capacity to deal with the situation.

The global scientific consensus, such as the IPCC’s 2002 report on impacts, adaptation, and vulnerability, speaks specifically to the situation of islands and areas where the elevation is very low. We are almost at sea level right here. Scientists project that the sea will rise, tropical cyclones will increase in strength, and we will see more effects from torrential rains, droughts, and extreme summer heat. This affects our infrastructure, our homes, as well as our physical and emotional well-being.

Local Challenges and “Slow Violence

In 2024, we conducted a survey (in collaboration with Buy-in Community Planning and the Climigration Network) in our community in which residents participated as researchers. We visited around 240 homes, specifically in areas prone to flooding and social vulnerability.

We asked: “If it were possible to receive an offer to relocate, would you be interested?” A little less than 50% said yes, but more than 50% said no. They want to stay in La Playa (communities) even though most are certain they will face flooding next year. This natural attachment to place is strong; roughly 40% of our residents have lived here for 40 years or more.

State neglect as “slow violence”

We also have a crisis of infrastructure.There has been a systemic disinvestment in water management, and our systems are obsolete. I am not an engineer, but I have eyes and ears in my neighborhood. My neighbors tell me this is a chronic problem caused by poor infrastructure and the practice of filling and compacting soil, which pushes water toward us.

I also want to highlight the work of theorist Nixon—different from the former president—who developed the concept of “slow violence” (Nixon, 2011). I urge you to consider that what we are experiencing as a community is, in fact, a form of violence—specifically, state violence, resulting from the government’s failure to address our ongoing problems. This violence is “slow” because it unfolds gradually, repeatedly impacting us over time. In communities facing environmental justice challenges, such as those living near industrial plants and factories, residents often become physically ill as a direct result of this continuous inaction and their exposure to hazards. I want to stress that what our neighborhoods are experiencing could be thought of as slow violence.

Redefining Resilience and Participation

The term “resilience” has been adapted by multiple disciplines (Muñoz-Erickson et al., 2021; Patel et al., 2017), resulting in 57 different definitions (Patel et al., 2017). This is a problem; if you cannot define it, how do you know you have achieved it? The dominant approach is that resilience is the capacity to recover or return to previous conditions after a shock. But that definition ignores equity, historical abandonment, racism, and structural inequality (Atallah, et al., 2019).

In marginalized communities, an acceptable form of resilience must move you forward and improve your situation, not return you to the same difficulties. Our goal through the VIDA Costera project is transformation: using adversity to create a new normality with more potential for justice.

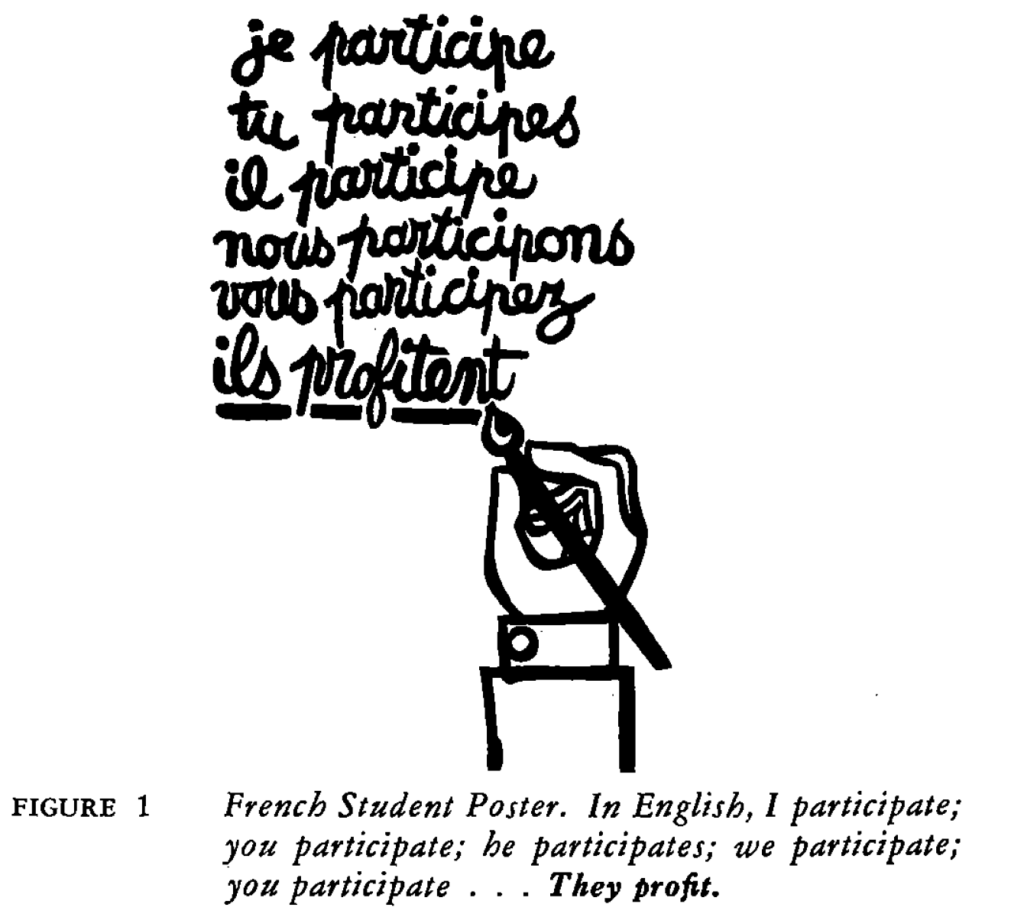

Regarding planning, resilience has often become an institutional ritual. There is a famous 1969 article by Sherry Arnstein regarding the “ladder of participation.” At the bottom, there is no real participation, only manipulation and “therapy.” Then there is “token” participation: consultation or information that often leaves a gap in actual power. What we do in our project is “Community Power,” where the community has control and delegates power.

Planning failures

Here are some examples of literature about technocratic mistakes in planning. When I say technocratic, I mean the person who goes to the university to study that topic and then applies that expertise in governance and decision-making. So, maybe you have heard of one: Pruitt-Igoe, public housing development in St. Louis, Missouri. What the planning promoted was a criminality, and a delinquency, and some major problems until the authorities demolished the building complex to solve the problem. Pruit-Igoe is an example of a failure in the planning of public housing, of what planning produced.

Another example from the 1970s: Love Canal in New York. A total of 800 homes were constructed over a hazardous landfill, which ultimately led to unfortunate consequences for all involved. That was the planning.

Another example, closer to home, is that of Mameyes. It is an example of a failure of planning. Lucilla Fuller Marvel, the planner who responded to that 1985 disaster in Ponce that left 130-some people dead in our city, wrote about what she found in Municipal planning documents. The municipal planning maps of the time did not document Mameyes. However, if one were to walk with map in hand to the end of Acueducto Street, you would see the discrepancy. You would have seen a neighborhood: Mameyes (Fuller Marvel, 2008). At the time, the Municipal plans did not treat the self-built neighborhood and the lives there as something significant enough to include on the municipal map. That was a failure in the planning when we look at the resulting tragedy.