Mamdani won with the support of the tenant class. But should he control their rent? Or redistribute it?

NY State Assemblyman and Democratic Socialist Zohran Mamdani has been declared the winner in the 2025 New York City Mayoral election, defeating Republican Curtis Sliwa and Independent Andrew Cuomo.

Mamdani’s campaign bore striking resemblance to that of Henry George, the political economist who, in 1886, ran for mayor on a platform confronting the same contradiction: a city bursting with progress yet mired in poverty. Like George, Mamdani named the problem of exorbitant rents. But he has not yet embraced George’s solution, which would address inequality while enhancing prosperity: the land value tax.

Photo from Mamdani’s victory speech

A Champion for the Landless

Mamdani won by building a new political coalition, one built on the economic anxiety of the working class. He was a champion of the landless–the class of folks in New York City who feel squeezed every month by land rents.

These folks have long been a strong majority of New Yorkers; by one estimate, nearly 70% of residents rent. Yet no one in establishment politics, no New York City mayor, has focused so keenly on winning this demographic. Until Mamdani. In the primary, Mamdani built an unprecedented coalition and won renter-heavy neighborhoods by a 12-point margin over Cuomo. He also brought new voters to the polls. Compared to the 2021 primary, renter-heavy districts in NYC saw a 40% turnout jump. The youth, a renter-heavy demographic who don’t see a path to land ownership, also broke heavily for Mamdani. In a Quinnipiac poll, 18-34 year old voters backed Mamdani 64-20 to Cuomo.

Mamdani won this class of folks by speaking directly to their concerns. He inspired the working class to imagine a city where their rent would be lower and their transit free. His campaign was hyper-focused on affordability, and regardless of how one feels about the soundness of his policies, the goal was clear: bring costs down.

At the same time, he tapped into populist sentiment. In a city as wealthy as New York City, why is there so much poverty? On Meet the Press, he pointed out the seeming paradox that New York City is “the wealthiest city in the wealthiest country in the history of the world, and yet, one in four New Yorkers are living in poverty.”

He built a base of local support, but spoke to a national audience that feels the same squeeze everywhere. A champion of the working class, when Mamdani walked the entirety of Manhattan, folks pulled up everywhere. In the past week, his rallies have attracted tens of thousands of attendees, a number unimaginable for a NYC mayoral race.

He did this during a time of deep distrust among both political parties, and of soul-searching for the Democratic party. The party’s brand has sunk to historic lows, with 63 percent of voters viewing the Democratic Party unfavorably, the worst rating in three decades. Pundits argue endlessly about whether the party has moved too far left or right, or whether it has lost touch with the economic concerns of working people. Mamdani’s campaign broke from that decline.

Rather than run as a party insider, Mamdani forged a new political coalition from the city’s renters and working class, and defied the gravitational pull of establishment politics. Whether Mamdani realizes it or not, New York has seen this kind of campaign before.

In the late 19th century, another mayoral contender also challenged the city’s economic and political order: the political economist Henry George.

The Economist who Asked the Same Question

From 1858 to 1880, George spent his teenage and young adult years in a rapidly ascendant San Francisco and was preoccupied with a paradox: why was the incredible economic and technological progress of his day accompanied by increasing inequality and poverty?

This was the concern of his 1879 book, Progress and Poverty, in which he observed that as society advanced and became wealthier, the benefits of increased productivity and innovation were captured by landowners in the form of rising land rents. This in turn drove the landless into grinding poverty and overcrowded tenement housing.

After moving back to New York City, George ran for Mayor in 1886 out of concern for the plight of New York’s landless workers, with a campaign bearing many similarities to Mamdani’s. Both took place in a period of economic turmoil and widening inequality, with the working class suffering unaffordable and substandard housing, offset against the luxury homes of wealthy monopolists. Both ran a campaign speaking to the economic anxieties of the working class against the backset of Democratic and Republican parties encumbered with corruption and corporate interest. Both called attention to wealth inequality in the city, forging a novel coalition of workers and tenants, as well as labor and socialist organizing. Both found particularly strong support in higher-density and migrant communities.

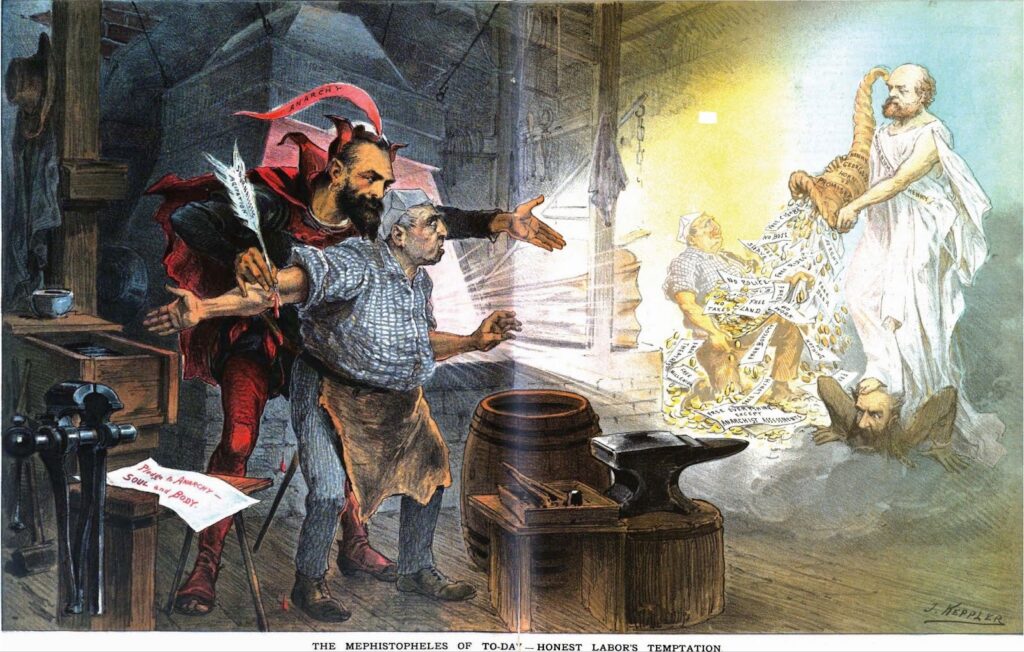

George and Mamdani’s opponents attacked and caricatured them in similar ways, by labeling them as naive utopians and bloodthirsty communists. In 1886, Joseph Keppler drew George showering a working man with ‘free rides’ and ‘no rent’. In 2025, Taylor Jones drew Mamdani walking a tightrope with ‘free buses’ and ‘freeze the rent’ adorning buildings around him.

Anti-George & Anti-Mamdani Cartoons by Joseph Keppler and Taylor Jones

The New Left Review echoes the comparison of George and Mamdani, drawing parallels between Mamdani’s walking the length of Manhattan and George’s march alongside 30,000 workers in his pre-election ‘monster parade’. Other commentators (e.g., here, here, and here) have also called out the similarities between the men in rhetoric, style, and electoral context. In essence, Mamdani understands the deep paradox underlying the wealth of New York City and has tapped into the same sentiment of George.

But do they have the same theory of the political economy?

Not entirely. At least not yet.

The Return of the Georgist Dilemma

Mamdani self-identifies as a democratic socialist and opponent of capitalism, and as such has proposed expansive new public services – universal child-care, free buses, subsidized grocery stores – funded by increases on corporate and personal income taxes.

But despite the labels Mamdani, his supporters, or his opponents apply to him, Mamdani is not uniformly anti-market. He recently acknowledged the importance of the private sector in supplying housing, for example, and wants to expand private sector housing production by, e.g., eliminating parking minimums.

Rather, Mamdani is critical of broken markets. He has been a vocal critic of at least two famously dysfunctional markets: the taxi and halal cart markets, which both require operators to obtain one of a fixed number of city-issued licenses. One of Mamdani’s earliest claims to fame was a viral video where he speaks to halal cart owners about the exorbitant rents they pay to incumbent permit owners. More recently, Mamdani has indicated he wants to increase the number of halal cart permits, undermining the artificial scarcity causing those rents.

The market that Mamdani is most known for critiquing, however, is the rental market. He campaigned heavily on rent control: legally barring landlords from increasing rent beyond some annual rate. Indeed, “freeze the rent” was the primary message on his website and campaign speeches.

“Freeze the Rent” was a core plank of Mamdani’s campaign.

In a market that suffers a dearth of housing units, Mamdani’s main policy stance is anti-market. The problem with rent control is that it disincentivizes housing maintenance and construction: landowners are less willing to maintain or build something when they can’t rent out (or sell) it for as much as they want.

Mamdani does acknowledge more housing is needed to meet demand and bring prices down. However, new construction takes years and therefore new supply does not immediately translate to lower rents for New Yorkers. Mamdani prefers to address people’s immediate needs with a populist tone.

But, Mamdani must provide a plan to create a fair housing market in perpetuity if he wants to make New York City affordable long term. He needs a plan for how NYC’s housing market can build enough to continue welcoming newcomers, where workers’ hustle enriches themselves rather than their landlord, and where tenants share in the city’s growth.

To do this, Mamdani must recognize the proper role of land. He has acknowledged that land is finite. On the Daily Show, he observed “[w]e obviously have a finite amount of land.” before arguing for increased housing density. And in one of his final campaign videos, he approvingly quoted 20th century East Harlem Congressman Vito Marcantonio: “If it be radicalism to believe that our natural resources should be used for the benefit of all…then I plead guilty”. But Mamdani has yet to articulate what the fixed supply of land, or the public right to natural resources, implies for policy.

If the halal market is monopolized by a fixed supply of permits which can be addressed by creating more permits, what can be done about the land monopoly when we cannot create more land?

Looking to George may provide the key.

Resolving the Paradox: Land and the Common Wealth

By George, landowners do not create the land value that drives land rents. Land is a natural resource whose value is created by nature itself or by the public and private investments around it, and its value should belong equally to all members of society. As such the way to resolve the land monopoly is to tax the value of land, a “land value tax”.

Mamdani has been outspoken about the power imbalance between tenants and landlords. As his campaign website puts it, “[O]ur city government regularly lets negligent and dishonest landlords off the hook.” When a New York tenant receives a lease renewal showing a 10 percent rent increase despite no improvement in building quality, the reason is not higher costs or better service. The reason is that landlords hold a monopoly over land.

Land is a finite resource, and its value rises as the city grows and public investment makes neighborhoods more desirable. The landlord captures this increase in value simply by owning the location. The building itself might deteriorate, but the land beneath it becomes more valuable every year. The result is that landlords can raise rents without providing anything new in return.

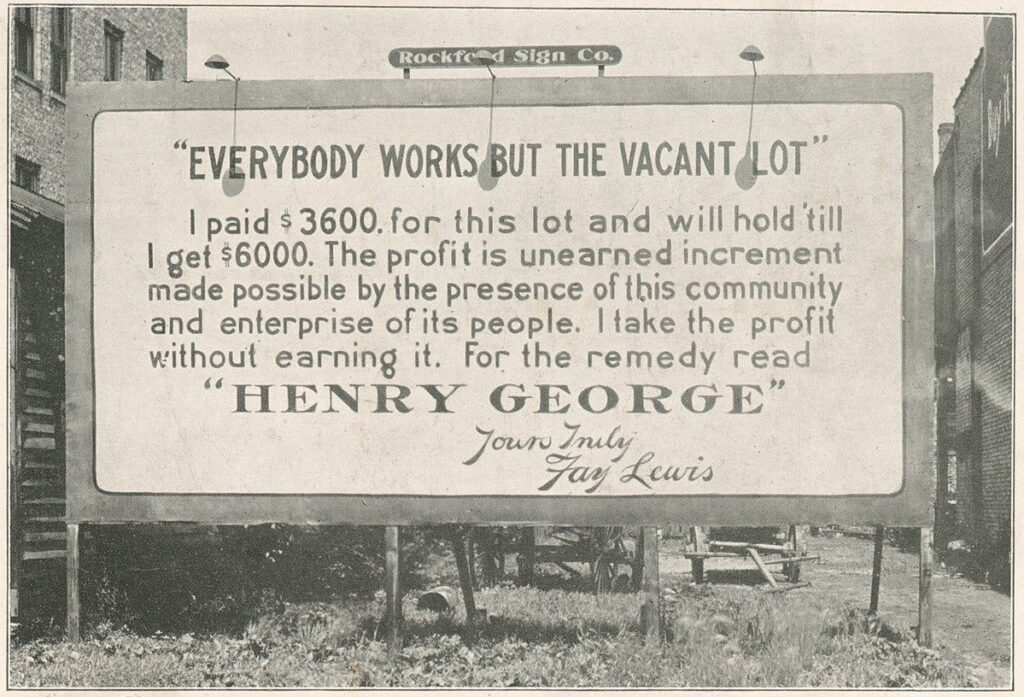

Georgist performance art by Fay Lewis in Rockford (Illinois), 1914

Henry George identified this dynamic as the root cause of urban inequality. He argued that because land value is created by the community, not by individual owners, the rent from land should return to the community through a land value tax. Collecting this rent for public use discourages speculation, encourages development, and ensures that the gains from growth are shared broadly.

Mamdani should shift at least some of his attention from rent control, to rent redistribution. In this sense, rent is not a housing cost; instead, it’s the annual revenue flowing to landowners who monopolize location.

In New York City, this would be accomplished through splitting property taxes into two taxes: a higher tax on the value of land and a lower tax on the value of buildings. By doing so, NYC would also see more development in prime locations. Throughout the 20th century, a number of cities in Pennsylvania shifted their property tax burden to the value of land, and empirical research suggests that those cities enjoyed increased housing supply, reduced sprawl, and increased economic activity in their central business district, among other benefits. It is therefore no surprise that today, economists across the political spectrum overwhelmingly support land value tax.

Mamdani has acknowledged that property taxes shape incentives. He stated the “property tax system…is broken” as it under-assesses and under-taxes property in wealthy neighborhoods with less dense housing, and over-assesses and over-taxes property in poorer neighborhoods with denser housing (an idea backed by research at the Progress and Poverty Institute). Mamdani’s solution to this problem involves tweaking NYC’s tax code in ways that are too complicated to get into here, but would ultimately, in his words, stop “penaliz[ing] rental apartments and the owners of those rental apartments” and instead “incentivize[s] the construction of rental apartments”.

The next extension is for Mamdani to acknowledge the negative incentives created by the building tax – less building – and the positive benefits of the land tax – less land speculation.

The possibility for a property tax shift to a land value tax is not far-fetched. The New York State Assembly is currently considering a bill enabling cities to pilot LVT. In large municipalities like NYC, the bill allows for pilots in just a subarea of the municipality, which, if passed, would give Mamdani flexibility to implement LVT such that it maximizes positive impact.

Mamdani has built a coalition among the landless much like Henry George in 1886, yet there is one major difference between the two: Mamdani won. Now, Mamdani must deliver on his promise of a fairer economy for all New Yorkers.

To achieve this promise, Mamdani should focus on redistributing land value to the city that makes that land valuable.

Russell Richie is Associate Director of Cognitive Science at the University of Pennsylvania, Treasurer of 5th Square Advocacy, and Vice-President of the Board at Progress and Poverty Institute.