Motivation

In what ways are environmental stressors re-shaping relationships among urban actors, and what are the implications for disrupting conventional patterns of urban growth?

Climatic extremes and associated disasters are increasingly shaping the future of urban development in the United States. In Central Arizona, now the site of the Phoenix metro area, water – its physical availability, its expense, and the infrastructure that has made it accessible – has always been central to the viability of human settlement. Over the course of the 20th century, the state of Arizona and its largest municipalities worked with mining and agricultural interests to develop innovative institutional arrangements to ensure water would be available for future urban growth. Federal funding enabled the construction of the Central Arizona Project (CAP), which brought valuable Colorado River water into the state. The Groundwater Management Act of 1980 created innovative institutional mechanisms to facilitate continued urban growth, particularly by requiring all new groundwater-dependent development to replenish any groundwater extracted, and to ensure a 100 year’s supply. The Phoenix metro area is now one of the fastest growing urban areas in the United States. But today, amid prolonged drought and tightening water supplies, the region is facing a defining challenge: Can a metro-region with growth as its engine continue to expand when its water resources are now being threatened by decadal-long drought and climate change?

This question is no longer theoretical. Shortage conditions on the Colorado River, because of declining snowpack and changing hydrological conditions, are forcing Phoenix area cities dependent on Colorado River water as the presumed sustainable and renewable alternative to groundwater to seek alternatives. And the state’s recent decisions to restrict new groundwater-dependent development—due to modeling results indicating shortfalls in meeting projected demand in 100 years —have sent shockwaves through local governments, real estate markets, and communities. In this pivotal moment, we – two researchers from Arizona State University and the Pacific Institute for Climate Solutions, respectively, set out to understand how water stress is changing the “rules of the game” for cities, developers, and residents alike. What can we learn from Phoenix about whether and how climate stressors are potentially reshaping the policies and social relations that have traditionally served as engines of urban growth?

Listening to the Valley: How We Did Our Research

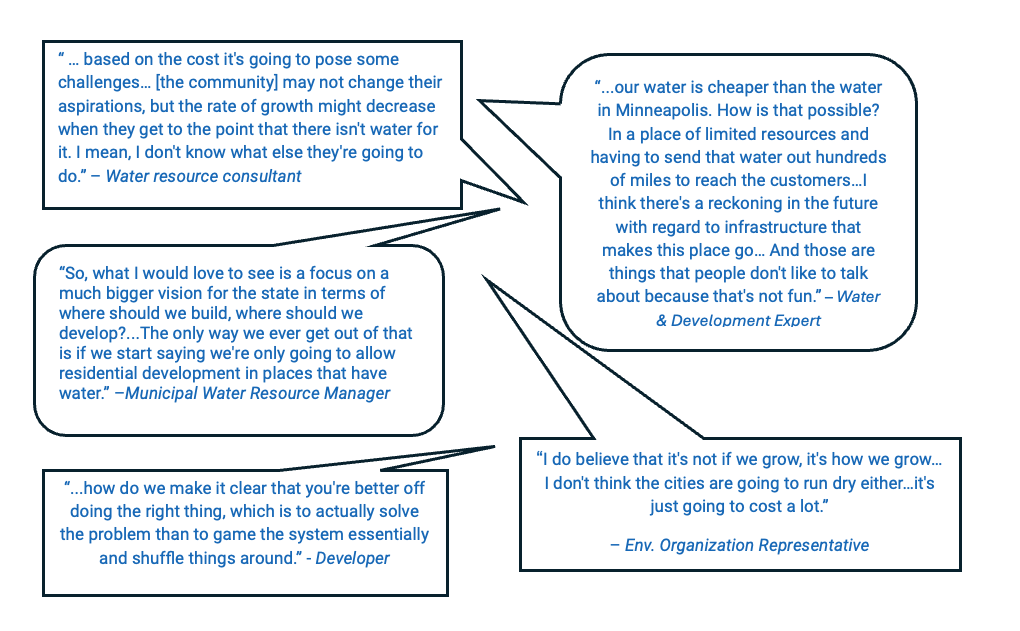

One of the challenges of doing research amid a “crisis” is that the dust has yet to settle on the subject of our study, and in such dynamic contexts, it can be very difficult to determine conclusively what the trajectory of change will be. The data is not yet available for any concrete metrics with which to measure the extent of change in social relations, or the definitive direction of policy reforms. Thus, we decided to capture how different urban actors were responding to the moment through a qualitative approach, drawing from a review of news media, policy documents, published peer-reviewed literature, and semi-structured interviews. The news media analysis allowed us an initial perspective into the dilemmas and debates around urban development and water emerging from policy actions in response to the drought. The media articles also identified key actors that we then recruited for interviews.

We conducted interviews with 35 individuals on the front lines of the water-growth dilemma: urban planners, water managers, land developers and brokers, environmental advocates, and policy experts. Our goal was not to identify a solution to the growth-water dilemma, but rather to understand how diverse actors perceive the crisis and what ideas and initiatives are emerging in response. The result is a snapshot of a region grappling with a profound shift in how it thinks about growth, risk, and differential responsibility.

What we learned: Shifting roles, responsibilities and potential collaborations

“So whether you’re the developer or whether you’re the property owner, it’s hard to tell someone I’m sorry, but you’re not going to be able to have the opportunity to get this financial gain because we don’t have water to serve for 150 years or 200 years. The longer the time frame, the harder it gets to make that argument. It’s just it’s tough.”

— Municipal water & development expert

For decades, Arizona’s robust water laws created a sense of security that fueled and facilitated development—especially on the metropolitan fringe where developers could take advantage of institutional arrangements that allowed them to draw on groundwater resources to build on raw desert land. They did this by paying into a fund that would then use surface water resources – often from imported Colorado River water — to replenish that groundwater. Although this arrangement was always contingent on the state’s periodic assessments of groundwater availability, this mechanism gave developers confidence that they had done what was required to secure water for their investment. After the moratorium on new groundwater-dependent growth became headline news in 2023, several of the development sector interviewees reported feeling betrayed by the state and anxious over the policy uncertainty surrounding their investments. Projected unmet groundwater demand – albeit 100 years into the future – coupled with the Colorado River shortages, revealed vulnerabilities in the system they had previously not had to confront. For some respondents, the risks were physical: a wakeup call to the potential that limited water supplies would ultimately serve to constrain growth; for others, the risks were more institutional: a realization that the water policies that they had relied on in the past to support their development investments were now diverging from their economic interests.

The moratorium was forcing both cities and investors to reconsider growth assumptions. Our interviews illustrated that peripheral cities like Buckeye and Queen Creek, which once relied on the state to certify individual development projects for assured water supplies into the future, were realizing they would need to take on more direct control over managing the water resource demand of developments within city boundaries. By becoming state-designated water providers, they would be able to reassure investors they had the water resources necessary to sustain future growth. Yet assuming this responsibility, just at the moment where water rights and water supplies were becoming more expensive and competitive, would be challenging, requiring difficult debates with current ratepayers about the value of future development and the appropriate use of increasingly valuable water supplies.

Our interviews indicated that in these circumstances cities are increasingly asking more of developers—demanding infrastructure investment, water sourcing plans, and even physical contributions to shared water budgets. This shift reflects a deeper reckoning: cities realize they may be held accountable by current residents if water security is compromised. New investments in infrastructure, necessary to move available water from rural to urban centers, or to support local replenishment of extracted groundwater, and to enable more effective storage and reuse of existing supplies, are also requiring collaboration. Novel public-private partnerships, inter-municipal collaboration, and increased support from state entities was widely considered to be essential for addressing the region’s water challenges moving forward. Yet how this collaboration would materialize was uncertain: the water providers and city planners we interviewed were aware of “haves and have nots” in terms of the legacies of past infrastructure investments, as well as in relation to physical and legal access to diverse water supplies.

The interviewees also raised issues that underscore the potential tradeoffs entailed in building urban resilience to water scarcity – particularly in a desert region. Meeting future urban demand is likely to come from retiring agriculture water rights and transporting water from rural basins for urban use. How water is acquired, by whom, and how to pay for the infrastructure needed has yet to be determined. The implications of urban water demand for the sustainability of rural communities is a subject of ongoing debate. Water, once an invisible backdrop to daily life, is also now front-page news. Current residents are increasingly asking city councils hard questions about whose interests are being met through growth planning, and how hard-won water resources will be used to meet current vs. future demands. This growing civic awareness could be a powerful force for policy innovation and long-term planning, requiring transparent debate over the benefits of growth and implications for the resources on which growth depends.

Lessons for the future

“There needs to be that political will to say no sometimes and say no, this area is going to be conserved because of water resources, and set aside, and we can develop and grow elsewhere or redevelop some areas that already have water allocation within that. But that’s big! It takes a lot of political will to do that.”

– Water resource expert

Importantly, the interviews revealed insights that could prove particularly useful for cities across the U.S. facing rapid growth vs. water security dilemmas. First, while some in the development sector were challenging the scientific basis and institutional legitimacy of the imposed restrictions on new growth, most interviewees strongly valued the certainty and consistency that the state’s water management institutions provided. Strengthening and even expanding, rather than weakening, these regulatory instruments was generally seen as the only path forward. Uncertainty in future water and climate conditions was almost perceived as a secondary threat compared to the uncertainties emerging from the policy context.

Second, while the responses described by interviewees suggest a slight shift in responsibility for securing water resources for new growth from the public to the private domain, respondents consistently underscored the fact that cities are ultimately responsible for the water security of the residents within their jurisdictions. This relationship above all means that cities must be empowered to effectively steer growth within their boundaries with long-term sustainability in mind.

Third, knowledge and information – particularly information on hydrological and climate science, as well as the complex regulatory context – is essential for city planners and water managers to effectively communicate with development sector interests, politicians, and the public in contexts of rising uncertainty. Sustainable development is unlikely without it. Academic institutions, technical consultants and regulatory agencies provide key roles in knowledge production and dissemination, necessary for grounding decisions in evidence.

Fourth, interviewees suggested that planning and coordination at a regional scale is what’s needed. The future of metro Phoenix is entangled in that of its rural hinterlands and vice versa; peripheral cities require coordination about growth and water needs with the cities in the metro core; and appropriate incentive structures are needed to equitably meet the needs of all who share the region’s critical water resources.

A way forward?

Phoenix finds itself at a critical juncture. The institutions and norms that once made the region a model for desert urbanism are under strain. Yet the interviews revealed that within this strain lies opportunity. Interviewees across sectors emphasized the importance of collaboration, science-based decision-making, and clear communication with each other and the public.

If Phoenix can harness these strengths, it may not only navigate this crisis but emerge with a more resilient and equitable blueprint for growth. As one interviewee put it, “We need a new metaphor for success—one that goes beyond expansion and instead values sustainability and shared responsibility.”