Local governments play a central role in the everyday lives of Americans. They provide a broad range of public services—from K–12 education and fire protection to emergency medical response, utilities, water conservation, policing, and even mosquito abatement (yes, there really is a South Cook County Mosquito Abatement District). These services are delivered by a complex ecosystem of local jurisdictions: counties, municipalities, school districts, and an ever-growing number of special purpose districts. As of 2022, the U.S. was home to roughly 91,000 local governments, which collectively employed 12.2 million full-time equivalent units and spent $1.86 trillion.

The geography of local governance is deeply fragmented. Some jurisdictions span multiple counties; others cover just a few blocks. Yet they share one common feature: nearly all raise revenue through property taxes. Each jurisdiction sets its own rate, and residents pay the sum of all overlapping tax rates where they live.

Since Charles Tiebout’s classic 1956 article, economists have often modeled local governments as single-layer jurisdictions providing a bundled set of services funded by a uniform property tax. In practice, however, the landscape is more complex. Local governments in the U.S. are horizontally differentiated—many services, such as public education, are provided by multiple, competing jurisdictions—and also vertically differentiated—any given household is typically served by multiple overlapping jurisdictions, each levying its own tax to fund distinct services.

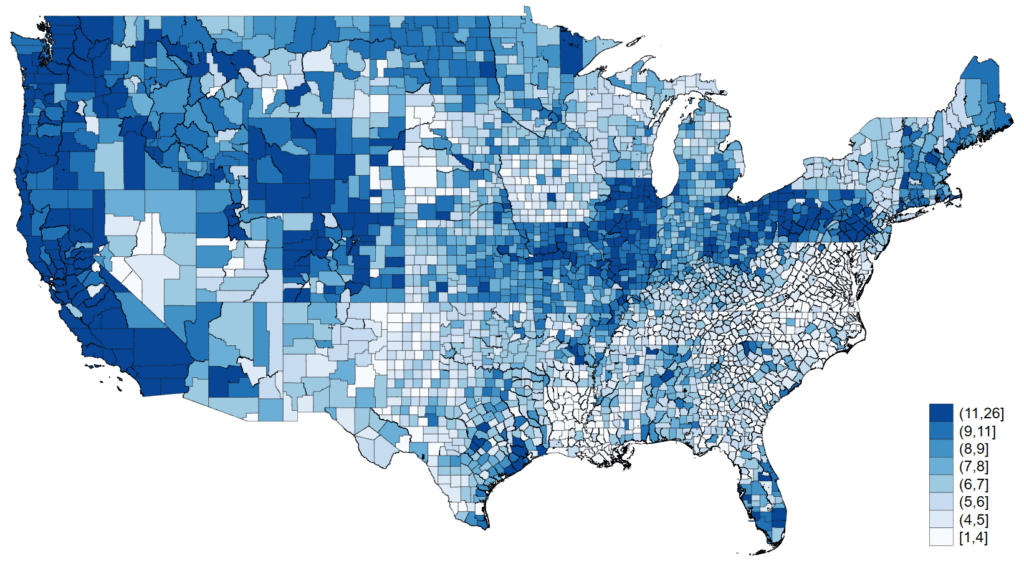

This vertical layering is not just a theoretical detail. As Figure 1 illustrates, it is a quantitatively significant feature of the U.S. system, particularly in the Midwest and Pacific regions. Understanding how this structure shapes public finance, service provision, and household behavior is a central focus of my research.

Notes: This map displays the number of distinct local government types that overlapped in U.S. counties in 2017. Local government “types” are counties, municipalities, townships, school districts, community college districts, fire protection districts, emergency medical services districts, park and recreation districts, as well as several other special purpose districts. Alaska and Hawaii are omitted. Source: author’s own calculations based on data from the 2017 Census of Governments.

In my paper, I show that this vertically layered structure of local governance can lead to inefficiencies. When a jurisdiction changes its property tax rate—for example, to fund new expenditures—the fiscal policy change typically capitalizes into housing prices. If the tax increase finances a desirable improvement, such as a renovated high school, housing values within the district may rise as the area becomes more attractive to prospective residents. Conversely, if the spending is perceived as low-value, property prices may fall, reflecting the mismatch between higher taxes and service quality.

This basic mechanism is well understood. What is less often recognized is that, in a vertically differentiated system, fiscal decisions by one jurisdiction can generate spillovers that affect others. Because multiple jurisdictions overlap geographically, a tax hike by, say, a school district can change local property values in ways that alter the tax base not only within the district but also in co-located jurisdictions. These interdependencies create fiscal externalities: households and governments outside the initiating jurisdiction—who have no voice in its decisions—may nonetheless face changes in tax burdens or service levels. This misalignment between decision-making authority and fiscal incidence may contribute to inefficiencies in the U.S. system of local governance.

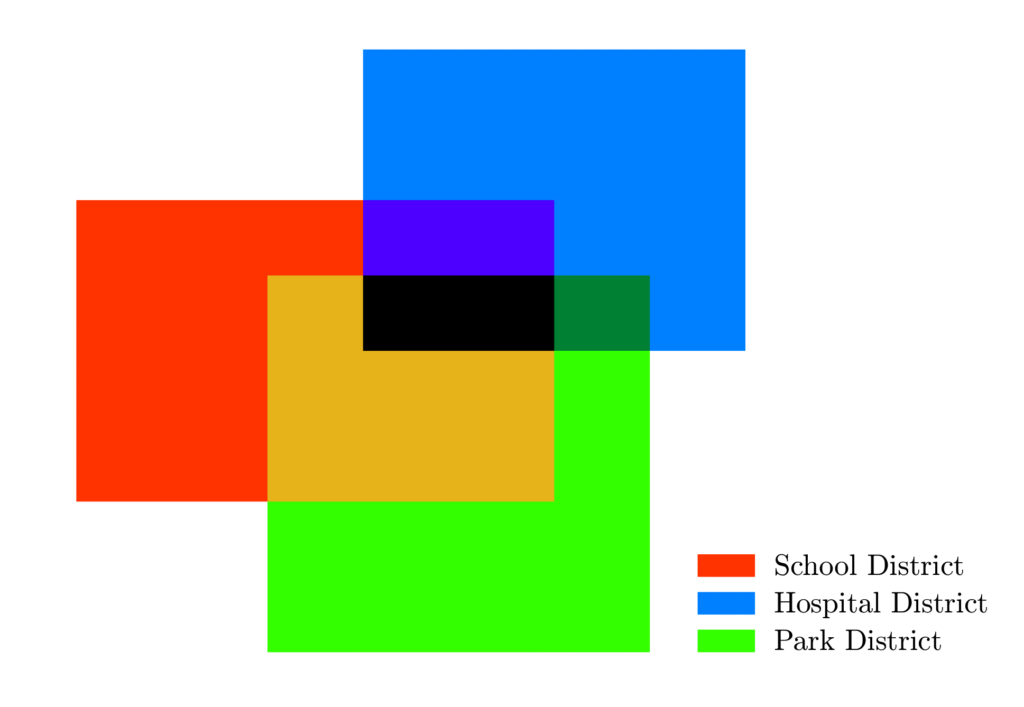

Notes: This figure is a stylized representation of overlapping local governments in the United States. Tax areas are implied by unique intersections of jurisdictions that provide different public services.

On the technical side, I develop a spatial equilibrium model of a metropolitan area in which multiple overlapping local jurisdictions share a common property tax base. Within each jurisdiction, heterogeneous residents vote over fiscal policy, choosing their preferred combination of taxes and public expenditures. This framework captures both the horizontal and vertical differentiation of local governments and allows for rich interactions across overlapping jurisdictions.

To quantify the model, I leverage a regression discontinuity design based on local referenda in which jurisdictions seek voter approval to raise property tax rates and increase spending. These referenda generate plausibly exogenous variation in fiscal policy near the approval threshold, which I use to estimate the effects of fiscal changes on key equilibrium outcomes: housing prices, population size, tax rates, and public spending. I then map these reduced-form estimates into the structural model, identifying the underlying preference and housing market parameters that rationalize the observed effects at the cutoff.

A central component of the analysis is a newly constructed, comprehensive georeferenced dataset covering all local government entities in the United States—counties, municipalities, school districts, and special purpose districts. The dataset spans from the early 2000s through 2022 and includes detailed information on property tax rates for each jurisdiction. To my knowledge, it is the most geographically granular dataset on U.S. local government boundaries and nominal property tax rates assembled to date.

With the model fully quantified, I conduct counterfactual simulations to evaluate alternative institutional arrangements. In particular, I consider a scenario in which vertically overlapping, single-purpose jurisdictions are replaced by horizontally differentiated, general-purpose governments that provide a broader bundle of public goods. Preliminary results suggest that this consolidation would increase household welfare by approximately 0.8 percent on average. These findings indicate that the current fragmented structure of local governments imposes efficiency losses, consistent with the argument advanced by Christopher Berry in Imperfect Union: Representation and Taxation in Multilevel Governments, which emphasizes how vertical fragmentation generates a fiscal common pool problem—encouraging over-extraction of shared tax bases by independent overlapping jurisdictions.